Emily Deshotels LaHaye was always at the center of the story of her husband’s murder. She was the witness, the last to see him alive; the only person to see the face of the man who kidnapped him.

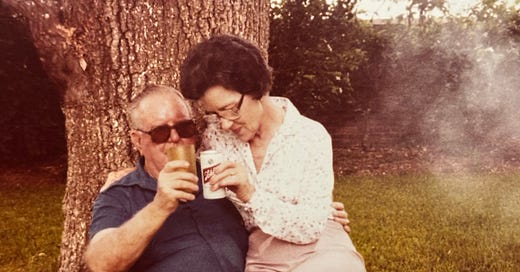

She was the one who knew Aubrey in the quiet privacy of his home, apart from the suits and the handshakes and the meeting rooms. She knew him in his pajamas, in the dark moments before they fell asleep, in the crusty eyed smiles of just waking. She knew what he smelled like in the crook of his neck, and the way he liked his rice and gravy. She knew what he worried about, and what thrilled him.

She was the one who lost the most.

Emily, for all of us, is the crucial window into not only the death of Aubrey LaHaye, but—after he was gone—his life.

For me, she is tangible in ways he never has been. Part of this is surely because Emily is someone who once held me. I’ve put my hand, as a trembling child, into her hands. I’ve kissed her face.

But she is also more real to me than he is, I believe, because she was a woman.

Even now, in the 21st century—a world so very different from the world Emily was a young woman in—I find myself ramming into the walls that would have kept me from knowing, really knowing, my great grandfather. That world of men. The world of women. Such walls, of course, have started crumbling in the years since his time at the height of Mamou’s social and political realm. But stepping back in time, I know where I would have been relegated. I know what he would have shared with me, what he would have held back.

But, Emily. Emily I believe I could know. Women have always been more generous with themselves, less precious with their legacies—partly because they are so often dismissed as less than legacy, freed from the public eye of history. More often, they become windows—transparent portals into another’s life. The irony of this is that without the burden of legacy, memory survives. Where Aubrey is memorialized in bronzed honor and generosity and genius—Emily is remembered as a woman of glorious contradictions. Many called her “Tam,” baker of beautiful breads. Others called her “Catin”—which can be translated into something derogatory, but in Cajun French is often used, with fondness, to describe someone with sass, attitude. She was a wearer of the trimmest, finest clothes. A woman who redecorated her entire house every few months on a whim. She was stern, and liked everyone’s nails to be trimmed and ears to be cleaned. She once shared with her granddaughter-in-laws, without a blink, that she and Aubrey scheduled sex, once a week. She would sing to her chickens, just before she killed them with a flick of the wrist, and make them into the best damn gravy you ever had. One of the things I remember about her most is that she’d perpetually be carrying a Ziploc bag of peanut butter fudge, a candy I can still taste on my tongue, even though I haven’t had it in almost twenty years.

In 1992, my aunt, Cindy LaHaye, was in nursing school studying geriatrics. As part of her final assignments, she was tasked with interviewing an elderly person and documenting how they had lived their life up until this point, how they had survived this long.

So, she decided to sit down with her grandmother-in-law, my great-grandmother, Emily, recorder in hand.

“Here you are at almost eighty years old,” she said to Emily. “And you are still here. You’ve been through hell, and you’ve made it. Age hasn’t gotten the best of you yet. It’s trying. But you’re a good person to write on, because even though life gave you everything you can think of in the world, you are still here to this day. And you’re fighting.”

Emily was seventy-eight years old at the time, and the preceding decade had taken her husband from her in a trauma unimaginable. She’d lost two brothers, two granddaughters, and her son. It was four years before I’d be born, before I’d know her—my stern, curly haired, impeccably dressed MawMaw who’d cut persimmons for us in the winter, who’d sit in her recliner and laugh while I performed my latest dance routine.

“You want me to tell you my life’s story?” she asked Aunt Cindy.

“I want you to start when you were born.”

In 1914, my great grandmother Emily was born along the Bayou Nezpique in a small community in Evangeline Parish called L’anse Grise, “Gray Cove”.

“I was a very poor little girl,” Emily began. She was the fifth of seven children born to Marcellus Deshotels and Atile Ortego Deshotels, who were 32 and 25 when she arrived. Marcellus was a sharecropper and a subsistence farmer— “he grew everything we ate, and he’d sell the excess to pay taxes and buy the few things we couldn’t grow.” They planted corn, cotton, sugarcane, and they made their own cane syrup. “We planted rice by the chance. That meant that if it rained, the rice would produce, and we’d have enough for the year. If it didn’t rain, it was converted to be pasture for the milk cows.”

Emily remembered that her father collected and preserved the seeds of his sweet potatoes and his sugarcane, that as a family they shucked, shelled, and ground corn for cornbread, and fed the rest to the livestock. Cotton was grown to sell, picked by the children. “We were a bunch of healthy children, so we all worked.” And in the evening, they all sat in the living room, where their father—a master storyteller and Cajun musician—regaled them with songs and tales told in the old language. Emily’s brothers, Ed and Bee, would later carry these stories and songs forth as Cajun musicians in their own right.

[Read a story told by Emily’s brother, Ed Deshotels, about the Bayou Nezpique, here.]

All seven children attended elementary and high school, and all seven graduated—a relatively rare achievement for a farming family in rural Evangeline Parish at the time. They were taught in English, the very last generation of this region to speak French first, the ones who have passed down the horror stories of bleeding knees and red wrists and hundreds of lines of “I will not speak French on the school grounds”.

Emily remembers first attending a two-room school for small children that was close enough to their home that they’d walk every day. Then, when they reached sixth grade, Emily and her siblings attended Vidrine High—a rural school started by Dr. J.C. Vidrine in 1910 to serve the surrounding agricultural community.

Vidrine High was six miles from the Deshotels farm—”Sometimes we walked, sometimes we had a horse and buggy, when they were not being used in the fields, like in the winter months,” recalled Emily. When she was in 10th grade, the school finally started offering the services of a “school bus,” which was likely at that time simply a farm truck decked out to operate like a wagon, seating dozens of children without a roof over the top.

Aubrey was one year older than Emily, and at a high school so small it operated almost entirely out of a single large room, they knew each other as soon as she started attending classes at Vidrine. They were officially going steady by the time he graduated in 1930, the single graduate at Vidrine High School that year. Despite his lone status, the graduation was attended by most of the local community, and featured several high profile speakers, including P.L. Guilbeau, the Louisiana superintendent of agricultural schools, and the school’s founder, Dr. J.C. Vidrine. Of the school’s fifty alumni at that time, forty-one were present.

Of the day, the Ville Platte Gazette reported:

“One of the prettiest settings on a platform, combining lattice work with draping vines, nasturtium flowers, and alternates of the class flower and motto, pleased an enthusiastic audience of close to 400 people at the Commencement exercises of the Vidrine High School.”

So the story goes, Emily and Aubrey’s relationship was so publicly recognized that she, as his girlfriend, was allowed to stand on stage with him as he received his diploma. According to the Gazette, both of them addressed that audience of 400, Aubrey in gratitude for his graduation, Emily as representative of the Junior class.

A week later, the Gazette ran a raving review of the Vidrine High School play Mudge—a work I can find not one drop of ink about on the internet. Aubrey performed as the nominal “Mudge,” and Emily Deshotels played “Venda Collins”.

That summer, Aubrey and Emily were listed as two of the two hundred young people from Evangeline and nearby parishes to attend 4-H camp at the Grant Walker Educational Center in Pollock, Louisiana—the very same summer camp that I would attend almost eighty years later.

By the time Emily graduated the following year, in a class of ten, Aubrey had earned enough money farming, working at the cotton gin, and assisting his father as a road contractor to buy sixty acres of land for cotton farming. “PawPaw,” Emily told Aunt Cindy, “I wish one of my grandchildren would be like him, because he saved as a little boy. Knew how to make money and what to do with it.”

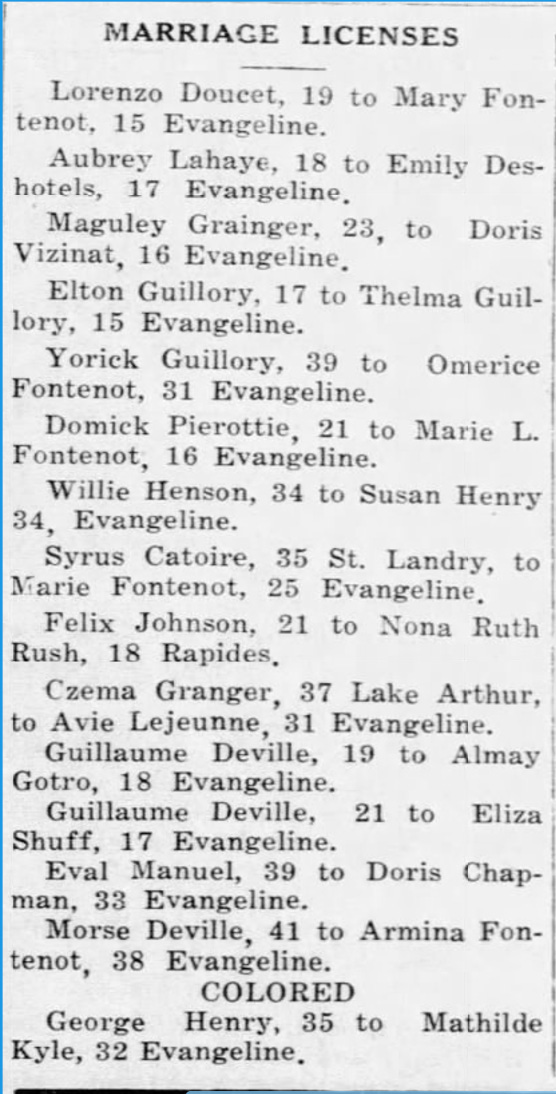

Emily married Aubrey the week after she graduated, in June 1931; he was eighteen years old, she seventeen.

Once they were married, Emily and Aubrey did not move straight onto their cotton farm, but instead rented it out. To bypass Louisiana agricultural laws prohibiting individual farmers from growing rice beyond a certain allotment, Aubrey’s father John LaHaye asked that the new couple move onto his rice farm on the Platin, where they would work as sharecroppers alongside family friends Leslie and Hazel Ardoin.

[Fun fact: Leslie Ardoin’s great granddaughter, Anne Christian Ardoin, is to this day one of my very best friends.]

“We cultivated the land with mules and plows, no tractors,” recalled Emily of that time. She told Cindy that she and Aubrey couldn’t afford a field hand, so Aubrey’s father John hired one. “We paid that man fifty cents a day.”

Because Emily had herself been raised on a farm, she found the daily tasks of her new life on the Platin to be no trouble. “It made it easy for me to survive the chores I inherited when I got married.” As she had all her life, she shucked corn to feed the mules, raised chickens, grew a garden. She did have to learn how to milk a cow for the first time, a task she had never taken on growing up “because I had enough brothers”.

During this time, Emily remembers that they “had nothing”. Aubrey and Leslie would make extra money by catching bullfrogs in the ditches to sell at market. “Our facilities at home were a pump on a well, a chimney, and a wood stove. We had no running water.”

Three years into their marriage, Aubrey and Emily had a son, Glenn Ferrell LaHaye. Emily recalls that she never saw a doctor until a few weeks before her due date. When the time came, the doctor came to her home and delivered the baby there. “A big healthy boy,” she said.

For nine days after the birth, Aubrey hired “an old lady” to come and cook for Emily, keep the house up, and care for the baby. “After nine days, I was on my own,” she said.

When Aunt Cindy asked Emily about breastfeeding, Emily told her a story: “When he was twelve months old, I decided to wean him. So, I tried, and he would not eat. I had never fed him, and he would not drink juice. He would not drink at all. He went on strike. He was losing weight, poor baby. So, one of my friends told me, ‘Give your baby back that breast.’ That Monday morning, after all we went through, I gave him my breast, and he sucked and sucked. He went to sleep, and every few minutes I’d go and check on him. He nursed until he was seventeen months old, and by then I’d learned to feed him in between.”

Three years later, Emily and Aubrey had another child, Flora Jane “Tot” LaHaye—“a baby girl, healthy and strong, no complications.”

Sometime shortly after my Aunt Tot was born, Aubrey and Emily finally moved to their original sixty acres in Reddell—purchasing more property in the process. “That first year, we grew 100 bales of cotton,” she remembered. The house they lived in, had been on the property already—two bedrooms, a dining room, and a kitchen. “There was no bathroom,” she said.

Here, on the road that would someday come to be called “LaHaye Road,” is where my grandfather Wayne was born in 1939. “He was healthy,” she says. “But I was huge. I don’t know if it was my blood pressure. If I had gone to the doctor during pregnancy, they would have probably put me on a diet.”

In those early years farming their own cotton crop in partnership with Leslie Ardoin and Aubrey’s brother Elvin, the LaHayes found quick success. “We had very little social life because we worked all the time. There was not much pleasure, but we prospered.” Aubrey was serving as the youngest-ever member of the Evangeline Parish Police Jury, and rising up in the ranks of half a dozen other local organizations. In 1942, he and Emily built one of the first brick homes in Evangeline Parish—a home that still stands today and continues to play a vital role in all of Aubrey and Emily’s descendants lives. We were all there just weeks ago, celebrating one of our family’s most recently engaged couples, in the very same kitchen where Glenn, Tot, and Wayne were raised; the same kitchen that Emily would prepare Aubrey’s lunch—a heaping plate of rice and gravy with three sides and fresh-made rolls—almost every day.

On this property, Emily famously oversaw a yard of chickens—which they raised for eggs and meat. My dad and his generation clearly remember her going out and killing them herself whenever a meal needed to be made.

Listen to my Uncle Richard describe how he remembers his grandmother Emily killing and cleaning a chicken for a meal.

There were hogs in the barn for lard and pork, cattle in the field for milk and hand-churned butter. Her vegetable garden was the envy of Reddell. “At that time, I considered myself a farmer, because I was at home taking care of the animals and the place while he was doing his jobs, which kept him away from home all day. He was home at night, but he was more interested in his businesses than his at-home.” She was a hostess to her core, the domestic half of Aubrey’s business enterprises—always ready to welcome Aubrey’s business associates, to kill a chicken for them and make a gravy. She hosted political dinners, fundraising events, rotary meetings, bridal showers.

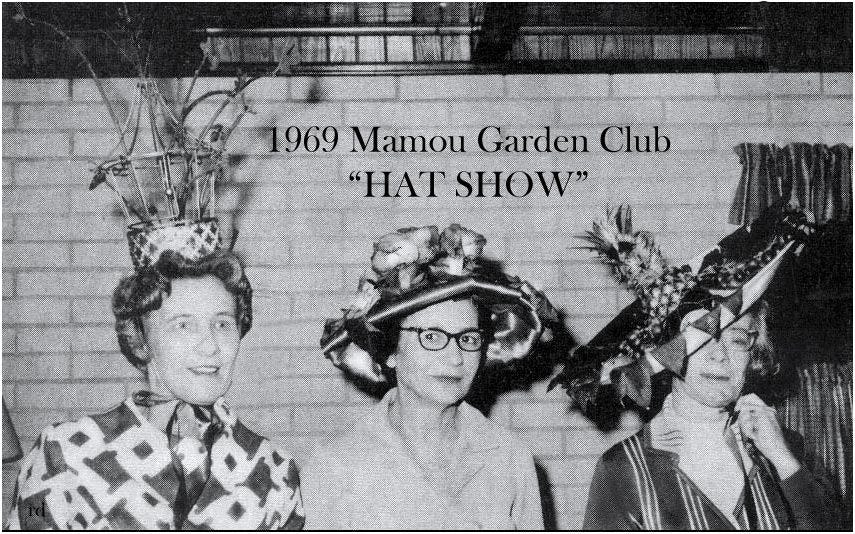

But as their children got older, Emily began to make her own name in the Evangeline Parish community, in the world of women that existed so very distinctly from the world of men in those days. She became involved, and rose often to leadership roles, in the Mamou Catholic Daughters of America, the Evangeline Parish Home Demonstration Council, the Evangeline Parish Cancer Society, the Mamou Garden Club, the Mamou Sewing Club, and the Evangeline Soil and Water Conservation District Stewardship Committee. She was elected to the office of the Ladies Auxiliary of the Louisiana Soil and Water Conservation District Supervisors. She presented demonstrations to groups on topics of cooking and gardening, organized fundraising events, and when Governor McKeithen opened up the “new Highway 13” in Mamou, Emily cut the ribbon.

One of my favorite archival finds in all this research I’ve done over the last decade is a photograph of my great grandmother Emily at the Garden Club’s hat contest, pictured in an absolutely ridiculous hat, with my husband’s great grandmother, Eula Guillory (also, in a ridiculous hat).

Emily didn’t mention any of this in her interview with Aunt Cindy, though. Instead, she went straight from her life “as a farmer” to her children, how proud she was of them—that they had all been selected as the “most outstanding” in their senior classes. “They didn’t have a valedictorian,” she told Aunt Cindy. “But they were all the ‘most outstanding’.” She spoke of how they’d all gone to college, done great things, then come home—and in the case of the boys, built homes on each side of her house on LaHaye Road. “They were all raised here, and they were excellent.”

Of her older years, when the children were grown and Aubrey had risen to the role of bank president, she said—”We were very healthy, both of us, and we enjoyed life. We had a very good life, very social. We were lucky enough to celebrate our 50th anniversary in 1981.

“And then in ‘83 . . .”

Here, Aunt Cindy interjects, “—devastation hit.”

“Yes.”

Next week, I’ll share the rest of my MawMaw Emily’s story, the hardest parts, told in her own words. If you aren’t already subscribed, sign up below to make sure that you don’t miss Part II.

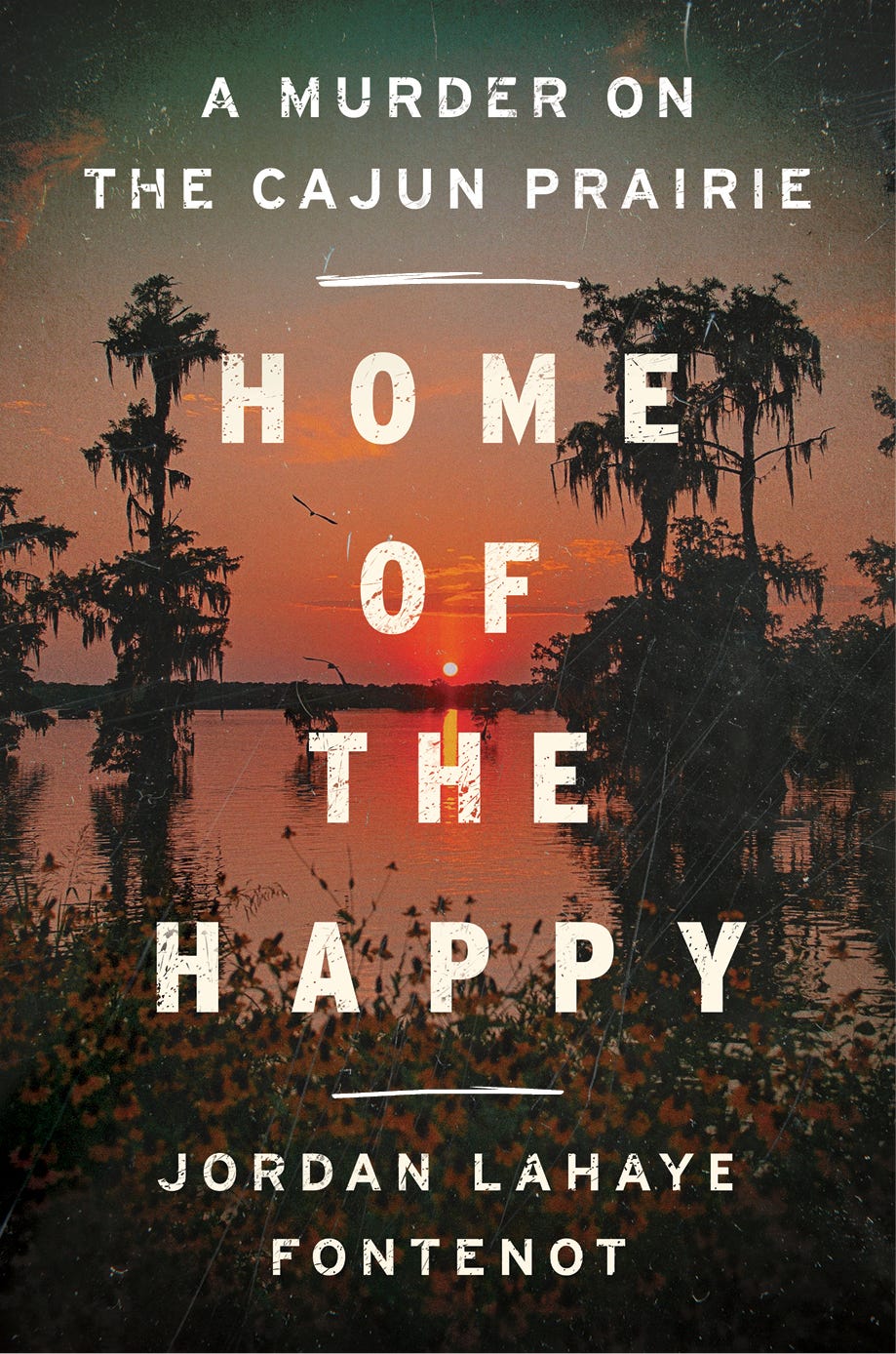

Book News

(Free) tickets are officially live for my book launch on April 1 at Cavalier House Books in Lafayette! From 5:30 pm–8 pm, join me and my dad, Marcel LaHaye, and James Fox-Smith, publisher of Country Roads magazine for a reading and conversation about Home of the Happy, followed by a book signing. Reserve your spot, and a book if you’d like (!), here.

Other Upcoming Book Tour Dates

April 2: Garden District Books in New Orleans, 6 pm

April 3: Cottage Couture in Ville Platte, 5:30 pm

April 4: Books Along the Teche Literary Festival—Shadows-on-the-Teche Visitor’s Center in New Iberia, 10:30 am

April 5: Mou Latté in Mamou, 9:30 am

April 8: Lemuria Books in Jackson, Mississippi, 5 pm

April 10: The Center for Louisiana Studies in Lafayette, 6 pm

April 12: NUNU Arts & Culture Collective in Arnaudville, 2 pm

April 16: East Baton Rouge Parish Library-Main Branch at Goodwood, 6 pm

April 25: Country Roads magazine launch—at the Conundrum, St. Francisville, 5:30 pm

April 26: Indie Bookstore Day at Cavalier House Books in Denham Springs, 1 pm

Jordan, I don't believe we've ever met but I'm one of the Vidrine Millers, living in Texas. I am awaiting your book publication and am enjoying this substack immensely. Every person you discuss is a flesh and blood memory to me. Your great grandmother will always be "Cousin Emily" in our house. Good luck with the book and I can't wait to get cracking on it