It’s been a year since I last published on this platform. A year since the manic invigoration of having done something so substantial as writing “the end” surged, and then quieted to a low hum.

I’ve never been great without deadlines, without oversight. It’s why I can only sustain a gym routine when I’m taking classes or on a team, why I—who minored in piano pedagogy—haven’t played the piano in years. I’ve always been externally motivated, a people pleaser to my core. Self-governance, who is she? I crave that coach, someone whispering in my ear, You can do better. You can move faster. You can do more. It’s probably why I made my hobby, my art, my career. Deadlines—they are how I structure my life, how I get anything done. The serotonin of having completed a task is what gives me permission to create. Without it, the imposter syndrome takes over—pressing down on my shoulders and telling me it’s all a waste of time.

So last year, having met that deadline of deadlines, I tried to give myself more—putting out these newsletters every other week. And it was working, for a while. For fourteen weeks in fact.

When people have asked me over the last year why I stopped, I’ve mostly blamed it on our puppy, Ziggy, who we adopted at 4 months old last May. There is some truth to this—those first few months with Ziggy were an overwhelm of scrubbing carpets and crate training and waking up three times in the night to let him outside. In the thick of my descent into the “puppy blues,” I missed one of my substack deadlines, gave myself grace. And then I missed the next one.

And then my book’s publishing date got postponed again (a story for another newsletter, perhaps).

And then I didn’t come back.

There is a secret among writers, shared not by all but by many of us who devote some piece of our lives to this craft. And it is that writing is dreadful.

George Orwell said it best when he wrote in 1946: “All writers are vain, selfish, and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives there lies a mystery. Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand.”

I’ve called myself a writer since I was small. I hold a memory of learning the word “author” in my kindergarten classroom, and immediately setting out to “write a book”—wherein I wrote out a hilariously misspelled transcription of the “Our Father” with accompanying illustrations, and stapled all of the pages together. Someone laminated the whole thing for me and I started passing it out to friends and family as “my book”. (This now strikes me as the ideal scenario for an author: plagiarism forgiven due to innocence. Having written without having to actually, you know, write.)

Ever since that debut, I’ve been grappling with that initial five-year-old conviction that I was a writer. My childhood bedroom holds a library of journals started and abandoned. Somewhere in the digital ether left behind by my family’s first desktop computer, an unfinished play about summer camp—inspired by the Mary Kate and Ashley book The Case of the Summer Camp Caper—languishes. There was a junior high “emo phase” defined by poems and lyrics written out in moody script—effusing a sadness I had absolutely never known. For my freshman year English class I wrote a poem, something experimental and strange. I read it to my mom and, when she crinkled her forehead, retreated to my room in a fit of “they’ll never understand me” angst.

By the time I got to college, though, I had lost all confidence in my practice, found my work mostly embarrassing and pointless. I set out with a Creative Writing concentration that was quickly abandoned. “What am I going to do?” I asked myself. “Write a book?”

This didn’t last forever, of course. As I shared in another essay last year, my junior year dropped me into a creative nonfiction course, where I felt as though something had finally clicked into place. In this genre, this style, I discovered that sometimes writing is less about having something to say than about asking questions, following where they lead.

This did not make the writing easier, though. Over the past decade of work I’ve produced, I don’t believe I’ve ever put anything down that did not emerge from a place of certain torment. From the first word to the last, there remains a sense of agonizing excavation. I’m pulling from a place that would prefer to remain unbothered. It’s never quite good enough, until perhaps one day it is. And I won’t know until I’ve already put in all the labor.

In the years between graduating from LSU and getting my book deal in 2021, I wrote very little new material for this book. I threw myself into the research, conducting interviews, digging through archives. I spent months transcribing a four-foot-tall pile of court documents. I edited the chapters I’d already written until they were unrecognizable. None of it was a waste, but almost none of it was writing the actual thing. I had so many excuses, good ones even. I had a job that required sitting in front of a computer for eight hours a day, writing and editing—which made it difficult to continue to use those parts of my brain after 5 pm. I had a wedding to plan. A new city to move to. A pandemic to navigate. My grandfather died. The world was falling to pieces.

The entire time, I lived with the guilt of unfinished business. It is no exaggeration to say that almost any moment I did not dedicate to work or something equally obligatory was overshadowed by the anxiety of : “I should be writing.”

This is part of what ultimately spurred me to seek out an agent, to get things moving. I needed some accountability. I needed a deadline.

And it worked, mostly. With an agent and an editor expecting pages, I spent most of 2022 devoting every spare minute I had to the book. Any four hour+ stretch available on the calendar was set aside. My husband went to bed alone most nights that year, and cleared out of the house on the weekends. When we bought our first home in the spring, I helped him unpack enough to get us functioning, to make our living room look decent and my office comfortable—and I shoved every piece of décor and art and extra furnishings into a closet to deal with after. Anything I did had to be weighed against the value of potential writing time.

There were undoubtedly more productive and healthier ways to have done this, but I didn’t allow myself the grace or time to explore them. There was a sense of panicked punishment about the whole thing—of penance. Every single time I sat down to work, I fought against an onslaught of instincts telling me to stand up, to do anything else. When I wasn’t working, I struggled in the real world too. I was living in a haze of mystery and family trauma and the intricacies of what happened in a courtroom in 1985. It was so difficult to think or talk about anything else. To carry on normal conversations. To get excited about anything at all.

Getting to the end was the hardest thing I’ve ever done.

The thing is, even after the book was finished, the dread remained. What are you going to do next? people ask me. Over the past year, I’ve scribbled down ideas and half-baked drafts for a dozen new projects. Novels, research, essays. This very newsletter. Fits and starts of inspiration and thrill buffered by some combination of laziness and fear. The demon hums in the back of my mind always, reminding me that life is passing by and the work remains, trapped, inside me.

What’s missing, of course, is a routine. A practice. This is what I have never managed to develop for myself. A regular, limited place in my life where my writing might belong. Haruki Murakami has said that when he is writing a novel, he religiously wakes up at 4 am, writes for about six hours, runs or swims, reads, then goes to bed by 9 pm. Joan Didion would sit around for most of the day contemplating what she might write, then finally get a paragraph completed by the evening. She’d sleep with the books she was working on. Lauren Groff wakes at 5, writes until the afternoon, then works on the “business” of being an author until the evening.

I, like most writers of today’s world, don’t have the luxury of doing this full-time—of dedicating hours and hours each day to my craft ( Though I do, I should note, have the just-as-rare luxury of writing regularly at my full-time job at Country Roads—for which I am grateful). I also, I’ll admit, at this stage lack the drive to totally sacrifice the things of life that I largely went without during that year of book writing: watching movies with my husband in the evenings, taking my dogs on leisurely walks, planting and killing vegetables in my garden, late nights drinking with girlfriends. So now I find myself seeking out balance, some space in between. Most successful writers dub that space the morning—where thoughts have yet to form in full and interruptions are quieter, darker; where possibility is the most potent. I’ve never been a natural morning person, but over the past year that puppy (ironically) has me waking hours before I must log in to work.

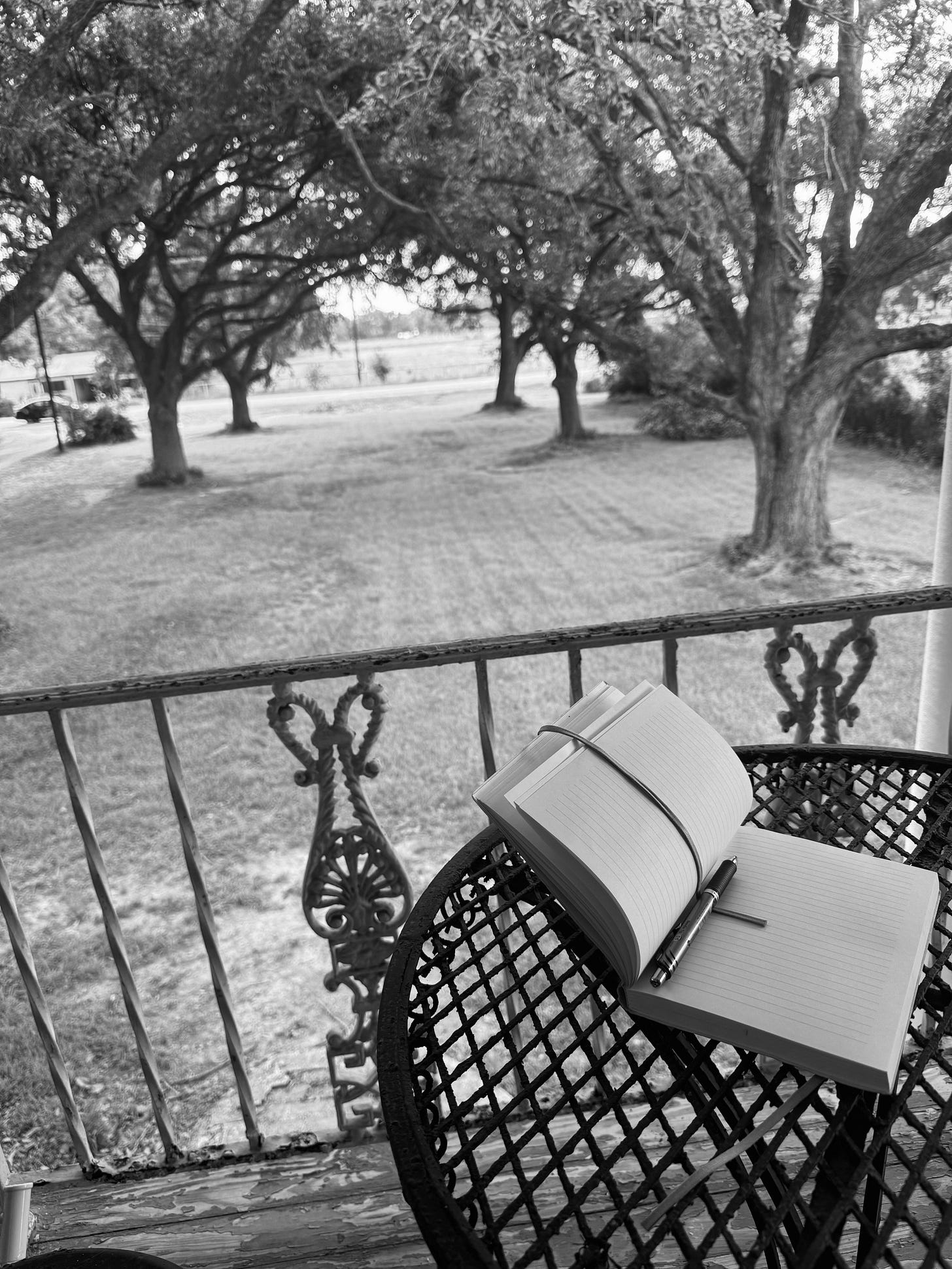

In the past few weeks, I’ve aimed to wake just a bit earlier than his 6:30 am whines, giving me time to sit with a journal. I’ve moved from the couch to the balcony, in all its wet heat, to the desk, to the kitchen table. It still doesn’t feel intuitive, and the dread has yet to lift. Maybe it never will. But words are getting written. I’ll keep trying, tweaking the routine until it sticks. I’ll keep showing up.

So in patience and grace, I ask you: watch this space. Thanks for being here.

You nailed it.

Jordan, I'm so glad I read this missive to better understand where you are in your

writing career. You're young, creative and a great writer. When your book is released you will enter a new, highly motivating phase in your vocation. Timing is everything. It will come and the writing you do for Country Roads will keep your skills up until that time. Shed the guilt and enjoy this moment.