In what I think must be my earliest memory, it is morning and I am wearing a pink robe with Pooh Bear’s face all over it. I love this robe, and feel fancy in it. I am in a living room, on a couch, with my mother and a baby, a brother. It must be Joshua. Morning light pours in from a window behind us.

It is strange because that memory is in a home I forget about, the starter home before my childhood home. We must have moved not long after this. The edges of the space are blurry, but bright. It’s one of those memories that you wonder whether it is even real—except that I know that robe existed. And I remember the feeling of wearing it.

My memory of childhood is a blur of play, contained within the smallest of worlds. I do not believe my concept of the universe extended past Mamou. I attended my preschool and then elementary school in Ville Platte. I spent summers in my grandparents’ pool, afternoons on the trampoline in the backyard. Petting horses, playing pretend, singing Kidz Bob versions of Britney Spears songs. Treasure hunting with a metal detecter in the pasture with my dad, planting green onions in the garden. My best friend was my cousin, and when I grew up I assumed I would live on LaHaye Road, where all the other grown ups I knew lived, besides my parents.

Today, when I visit LaHaye Road, things are different. My grandparents, into their eighties now, no longer join us in the pool or in the cattle pen, no longer prep spontaneous coffees or rice & gravies. As my world continues to expand beyond this prairie, theirs has grown smaller, mostly confined to the recliners where they rest the days away. I visit and they smile and they tell me they love me. They still remember me, but only just. They have forgotten so much else.

Only seven years ago I sat before them and collected their memories for this book. As Aubrey’s last living son, my Papa’s memories were some of the oldest, the most precious. His sharing of them with me preserves them for another generation.

As his memory now wanes, I think often of my memories of him. And how it is now in this place I find myself between the blurry worlds of childhood and the fading land of old age that the responsibility of memory weighs the heaviest. Where it is the most important, where we must hold not only our own memories but those of the children who won’t recall their sweet beginnings and the elderly whose lives are no less significant just because they have forgotten them.

I think also of how holding memory in the isolation of one’s mind is to keep those memories vulnerable, susceptible to being lost forever. Memories are meant to be shared, in writing or in conversation; that is the only way they find space in the present, and in the future. Even when they are imperfect.

People are alive so long as they are remembered, they say. I hope to keep my people, even the ones I never knew, alive for ages.

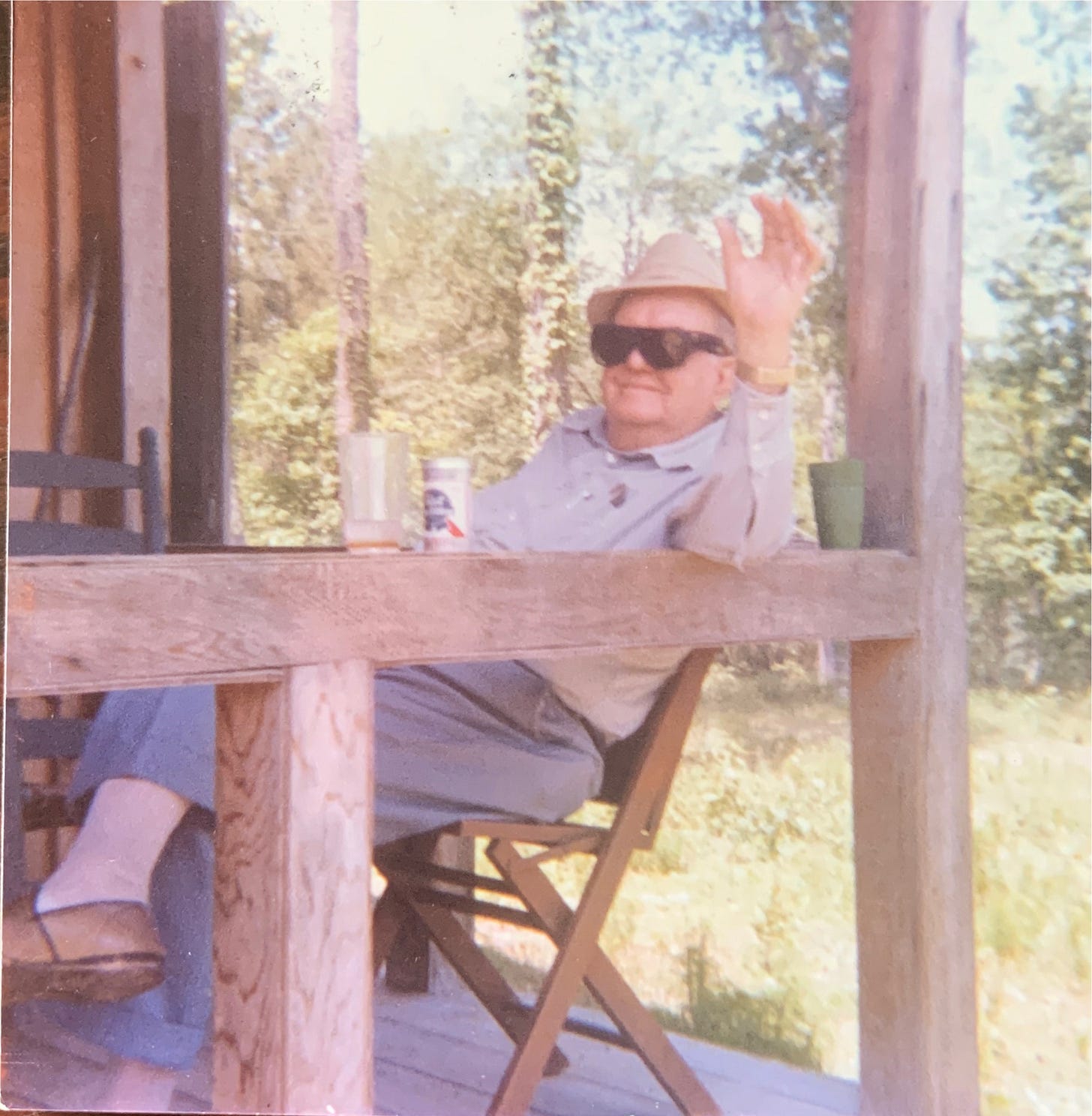

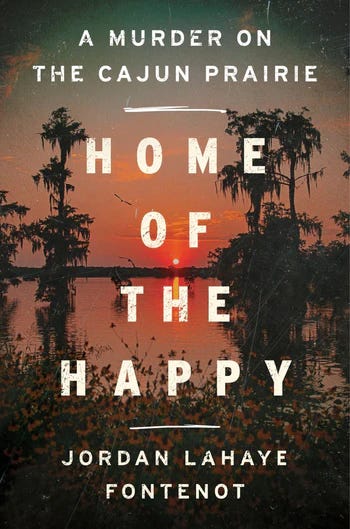

Watch this interview with my Papa Wayne by Parish Road Media, in which he shares memories and tells stories of his Uncle “Be” Deshotels.

Memory runs through HOME OF THE HAPPY like a thread, connecting bits and pieces of the past together, strong and taut in some places, frayed in others. I’ve relied so much on the memories of others to piece together the events of January 1983, and all that came after. Some memories are contradictory, some impossible, some uttered from beneath the gauze of forty-years-gone rumor. Most are impossible to fact check. Many are repetitive, almost insignificant. Some punch you in the gut with their implications, their devastations. The lingering disbelief—How can this have truly happened?—sharpens the memory for some, dulls it for others.

Memory is all I have of Aubrey, of who my great grandfather was. Of what was lost. By the time I was old enough to ask, most memories of him before his grandfatherhood had faded to ghosts—the child Aubrey all but lost to the wind, the young ambitious farmer only the barest of bones. The Aubrey I encountered, in his living descendants’ memories, had accomplished enough for a lifetime, had built it all already. He stood as a pillar, rice-and-gravy bellied and cigar hanging from his mouth, for our family. He advised his children, bought ice cream and watermelons for his grandchildren. Ate, with relish, the incredible food his wife prepared for him. He was PawPaw.

Memory arises in more consequential places, too, of course. The conviction of John Brady Balfa, who is now serving a life sentence for Aubrey LaHaye’s murder, hinged significantly upon my great grandmother Emily’s memory of that awful day he was taken. January 6, 1983.

During the ten days in between the kidnapping and the murder, half a dozen law enforcement officials interrogated her, again and again, about the details of the worst twenty minutes of her life. “How tall was the kidnapper?” “What was he wearing?” “What did the knife look like?” “What color were his eyes?” Her descriptions of the man and his time in her home came to be the heart of the case, the face she described sketched out by FBI composite artists, and plastered around town. The faces they created, though, she insisted were never quite right. But MawMaw Emily’s memory, at this point in the investigation, was literally the only significant evidence they had to go on.

It was not until September of 1984 that certainty found her. When she looked at a lineup and pointed at John Brady Balfa, saying “May God forgive me, that’s him.” She saw his face, and she remembered it.

Today, studies have shown that witness identification does not carry the weight of truth that you’d think. Our memories are mysterious, capturing some things, letting loose most others. And what they hold onto tends to be more of a rendering than a photograph, susceptible to the fade of time, to the influence of storytelling. Our memories are living documents that are ever dying, and they cannot always be trusted. Research has revealed that in moments of trauma, of fear, of stress—people’s memories do not always retain details perfectly. Since the introduction of DNA testing into the world of criminal investigations, hundreds of wrongful convictions have been revealed by the hard-fast proof of genes. About 69% of those wrongful convictions involved erroneous identifications from witnesses.

The case of John Brady Balfa and Aubrey LaHaye spools out into something far more complicated than this single issue. But here is where my questions began: with my MawMaw, standing eventually before a jury, pointing right at Balfa and saying, “That is the man who took my husband.” She was confident, she was sure. She never questioned it for the rest of her long life. The people who knew her, who loved her—they believed her. They saw truth in her memory. Certainty. Resolution.

But what if she was wrong?

Jordan’s words resonate with me so much:

“I think also of how holding memory in the isolation of one’s mind is to keep those memories vulnerable, susceptible to being lost forever. Memories are meant to be shared, in writing or in conversation; that is the only way they find space in the present, and in the future. Even when they are imperfect.

People are alive so long as they are remembered, they say. I hope to keep my people, even the ones I never knew, alive for ages.”

Beautifully written