Man, I love a late Mardi Gras. The sheer luxury of having almost all of February to prepare my mind, my liver, and my costume is unmatched. Valentine’s Day even gets its own twenty-four hours in the sun (well, okay—we ordered the Rock ‘n’ Sake Sushi King Cake, so . . . ).

I’ve been running courirs for almost a decade now. I was dragged to my first by an old boyfriend, skeptical and tired from a long weekend of drinking on the streets of Mamou. My friend and I bought costumes from a thrift shop the day before the run, carrying them around with us into the bars on Sixth Street, soaking them in cigarette smoke. And at 6 am, we dragged our sorry hungover asses out to Eunice.

Growing up, Mardi Gras was something we observed—something the grown-ups did, something the men did. We’d watch the shenanigans of Mamou’s courir play out in my uncle’s yard every other year, eating our crawfish from a safe distance and shaking our heads in amazement at the muddy, masked men dancing on their horses.

That first courir I took part in, though, was a day of total wonder. We joined a “krewe” of friends and acquaintances (well, and strangers too) on a hay trailer following thirty or so other hay trailers and schoolbusses and other folk “floats”, all behind the armada of “true” Mardi Gras on horseback, meandering through the rural backroads of Eunice all the live long day. They’d let the chickens loose in the crawfish fields, the most ambitious of our comrades splashing through the water to catch them. At one point, someone picked a recliner out of the ditch and put it on the trailer, and we all took turns napping in it as the procession wound its way across the prairie.

I wrote about the magic of that day, and the Mardi Gras days that followed, for Country Roads some years back:

There’s a point, skipping down a dirt road along some remote field in Eunice, capuchon hanging sideway around your neck and a link of boudin in hand, where you quite simply lose time. How long have you been on this journey? What was life like before, exactly? How could you have ever gone a day—in that past life of yours—wearing anything but this animated suit of scrappy, rainbowed fringe so perfectly designed for dancing? How many Bud Lights have you had, anyway? You turn, shade your eyes, and yell at some passing compagnon, covered in mud from chasing a chicken into the crawfish lake, “How far back is the beer truck?” . . .

In the years that followed, I met my husband—whose family had emigrated from Mamou to Lafayette before he was born. It had been years since he’d been back to Evangeline Parish. That first Mardi Gras together, we hardly knew each other. But hand-in-hand, backpacks full of jello shots, we headed back home.

Saturday morning: bloody Marys and dancing at the historic Cajun music joint, Fred’s Lounge in Mamou—a morning which stretches across the entire day, popping in and out of the bars on Sixth Street, many of them which open only once a year.

Saturday night: gumbo at my cousins’ house down the street. This is where many of my family members met Julien, my new ponytailed, tattooed boyfriend, for the first time. He was very drunk, but so were they. My aunt Suzette pulled me to the side and whispered in my ear, “that beautiful hair!!”

Sunday: on to Church Point, where we set up on the side of the road with our ice chests and awaited the parade (they do real floats in Church Point, in combination with a traditional courir—they also, controversially, throw beads).

Sunday night: To Henderson, to hear Julien’s uncle Steve Riley perform with the Mamou Playboys. We dragged my family along, and some of his, to two-step and eat our weight in fried seafood until late into the night.

Monday: A day of desperately needed rest.

Monday night: Back to Mamou. Geno Delafose was playing “Chickens on the Run” on the far side of the street, and Julien and I were throwing down raw oysters at the annual Savoy Hospital fundraising banquet. Later, we’d go out to the stage, and—the bad dancers that we still to this day are—he’d spin me in such a way that the ring on my pinky finger flew out onto the pavement, forever lost to Sixth Street. The night ended at LakeView Park & Beach down the road, where Steve Riley’s accordion was once again leading the crowd in the Mamou anthem, “La Danse de Mardi Gras”.

And then, somehow, at 6 am on Tuesday, we got ourself up to run the Eunice courir.

That year, I drove back to my home in Baton Rouge and immediately came up with the flu. I’d run myself absolutely ragged. But we’d return together the next year, and the next, and almost every year since.

The schedule’s gotten lighter now, for us. We no longer hit every stop, though we’ve added a few, too—Lundi Gras at the Holiday Lounge, for one, is one of the most dazzling expressions of Mardi Gras culture I’ve ever been a part of. One year, Julien ran the Mamou courir—a day spent entirely on horseback, guzzling beers and making mayhem, a true rite of passage for any man of Evangeline origins. These days, we typically spend the Tuesday running the Faquetaigue courir—a more progressive and inclusive expression of the tradition that, over the past twenty years, has grown into one of the most popular Mardi Gras in Acadiana.

When January comes around there’s always a conversation between Julien and I about skipping it all together—“we’re getting too old,” Julien says. But then we inevitably find ourself back on Sixth Street Saturday Gras morning, dragged into the delirium.

As a writer captivated by legacy and tradition within our hyper-regional culture, Mardi Gras is one of those things that I’ve returned to, again and again. Over the years, I’ve written half a dozen stories about the courir—the wonder and the mystery and the impact of it. There are few other rituals in our modern world that can hold so much—this (literally) intoxicating expression of history, this tribute to our ancestors crafted from rags, rolled in mud, and rooted in traditions of generosity and play. Gosh, there are so few opportunities for grown people to just play today—to go feral, to dispense of all the responsibilities and burdens of daily life, just for a few hours. In the bright afternoon light of winter’s end, the beer gone to your head and your identity obscured, there is no one telling you not to shout from the ecstasy of it. The grass is greener than ever before, and the boudin has never, ever tasted so good.

I’ve written before about the all-too-tangled worlds of small town Louisiana, about how the family trees intertwine with the stories and the songs.

Mardi Gras itself connects the families at the center of my book, Home of the Happy, through song. “La Danse de Mardi Gras” is one of America’s oldest folksongs, heard blaring through the speakers at this time of year across Acadiana. The reason that we know the words is because in the 1950s, a folklorist wrote them down, per the recitation of my great great grandfather Marcellus Deshotels, Emily LaHaye’s father, Aubrey LaHaye’s father-in-law.

La Chanson de Mardi Gras

Capitaine, capitaine, voyage ton “flag.”

Allons se mettre dessus le chemin.

Capitaine, capitaine, voyage ton “flag.”

Allons aller chez l’autre voisin.

Les Mardi Gras se rassemblent une fois par an

Pour demander la chèrité.

Ça va-z-aller-zen porte en porte.

Tout a l’entour du moyeu.

Les Mardi Gras viennent de tout partout.

Ouais, mon cher bon camarade,

Les Mardi Gras deviant de tout partout;

Mais tout a l’entour du moyeu.

Les Mardi Gras viennent de tout partout,

Mais principalement de Grand Mamou.

Les Mardi Gras viennent de tout partout;

Tout à l’entour du moyeu.

Voulez-vous reçevoir

mais cette bande de Mardi Gras?

Voulez-vous reçevoir

mais cette bande de grands soulards?

Les Mardi Gras demandent la rentrée

Au-maître et la maîtresse.

Ça demande mais la rentrée

avec tous les politesses.

Donnez-nous autres une ‘tite poule grasse

Pour q’on se fait un gumbo gras.

Donnez-nous autres un ‘tite poule grasse

Tout a l’entour du moyeu.

Donnez-nous autres un peu de la graisse,

S’il vous plaît, mon carami.

Donnez-nous autres un peu du riz;

Mais tout a l’entour, mon ami.

Les Mardi Gras vous remercient bien

pour votre bonne volonté.

Les Mardi Gras vous remercient bien

pour votre bonne volonté.

On vous invite tous pour le bal à ce soir;

Là-bas à Grand Mamou.

On vous invite tous pour le gros bal;

Tout à l’entour du moyeu.

On vas invite tous pour le gros gumbo;

Là-bas à la cuisine.

On vous invite tous pour le gros gumbo.

Là-bas chez John Vidrine.

Capitaine, capitaine, voyage ton “flag”.

Allons se mettre dessus le chemin.

Capitaine, voyage ton “flag.”

Allons aller chez l’autre voisin.

Listen here to hear the song sung by Bee & Ed Deshotels:

Marcellus’s twin sons Bee and Ed (Emily’s younger brothers) were the first to ever record the song. Not long after, The Balfa Brothers would begin their ascent to fame on the global folk festival circuits, introducing Cajun music to much of the world for the first time. Their version of “La Danse de Mardi Gras” is still to this day considered canon and played on the local radio all year long.

John Brady Balfa, the man convicted of killing Aubrey LaHaye, is the son of Balfa Brothers bandmember Harry Balfa, nephew of the famed Dewey Balfa.

And then the thread trails further, following me into my new family. My husband’s uncle and godfather, Steve Riley, emerged with the most popular rendition of “La Danse de Mardi Gras” of all. It’s the one I grew up hearing, the one we chase from the street in Mamou to Pat’s in Henderson to Lakeview each Mardi Gras season.

As I wrote in an article on the song’s history once:

Against the wild energy of a medieval melody so familiar we felt we must have known it since long before our time, we’d clap our hands, stomp our feet. The rhythm of the song is malleable—as attuned to the human heartbeat as to the gallop of horses. Played fast, especially on the accordion, it lifts an audience into each other’s arms, feet keeping time, so very easily. Played slow, the lyric Donnes-nous autres une tite tres up peu de la graisse / Pour q’on se fait un gombo gras (“Give us a little fat hen so that we can make a fat gumbo”) can practically bring a grown man to tears.

Find some of the articles I’ve written on Mardi Gras over the years below:

The Begging Song of Grand Mamou

How one of the oldest songs in America lives on

For the Oxford American, I wrote about the history and cultural impact of the “Mardi Gras Song,” traditionally known as “La Danse de Mardi Gras”—and my own ancestors’ roles in its preservation.

Mardi Gras, On Foot

Stepping in time with the most whimsical walks of the season

In this story for Country Roads magazine, I and four other writers shared vignettes of our experiences walking Mardi Gras in parades from New Orleans to Lafayette to Eunice.

Chasse-Femme

For this woman-led Courir de Mardi Gras, Prairie des Femmes erupts in a chicken chase

In this story for Country Roads magazine, I wrote about the woman-led courir that took place for a few years in the Prairie des Femmes; and the way its departure from gender-based tradition was inherently within the ritual of subversion that is at the heart of Mardi Gras.

The Mamou Insider

We’d like to lead you on a wild chicken chase

For this Country Roads story, I was commissioned (before I worked there) to share all my local know-how as a guide for visitors considering an excursion to Mamou’s Mardi Gras traditions.

Last year, I got a message from a reporter from VICE magazine—an Alabama native living in New York, who had found my “Mamou Insider” article. Jackson Garrett and his team had planned to create a documentary on Mardi Gras traditions along the Gulf Coast, featuring celebrations in Mobile, New Orleans, and Cajun Country. He wanted to know what he needed to do to experience an authentic courir. By the time we finished talking, he had abandoned his plans for Alabama and New Orleans, and shifted the documentary to focus exclusively on the strange and wild tradition of the courir in South Louisiana. I told him that to capture it, he’d have to enter right into the fray. He’d have to run.

That documentary, called the VICE Guide to Mardi Gras, will air on VICE Youtube on February 18. After that date, you can watch it at the button below and in the meantime, follow Jackson on Instagram to see excerpts in the days leading up to the release!

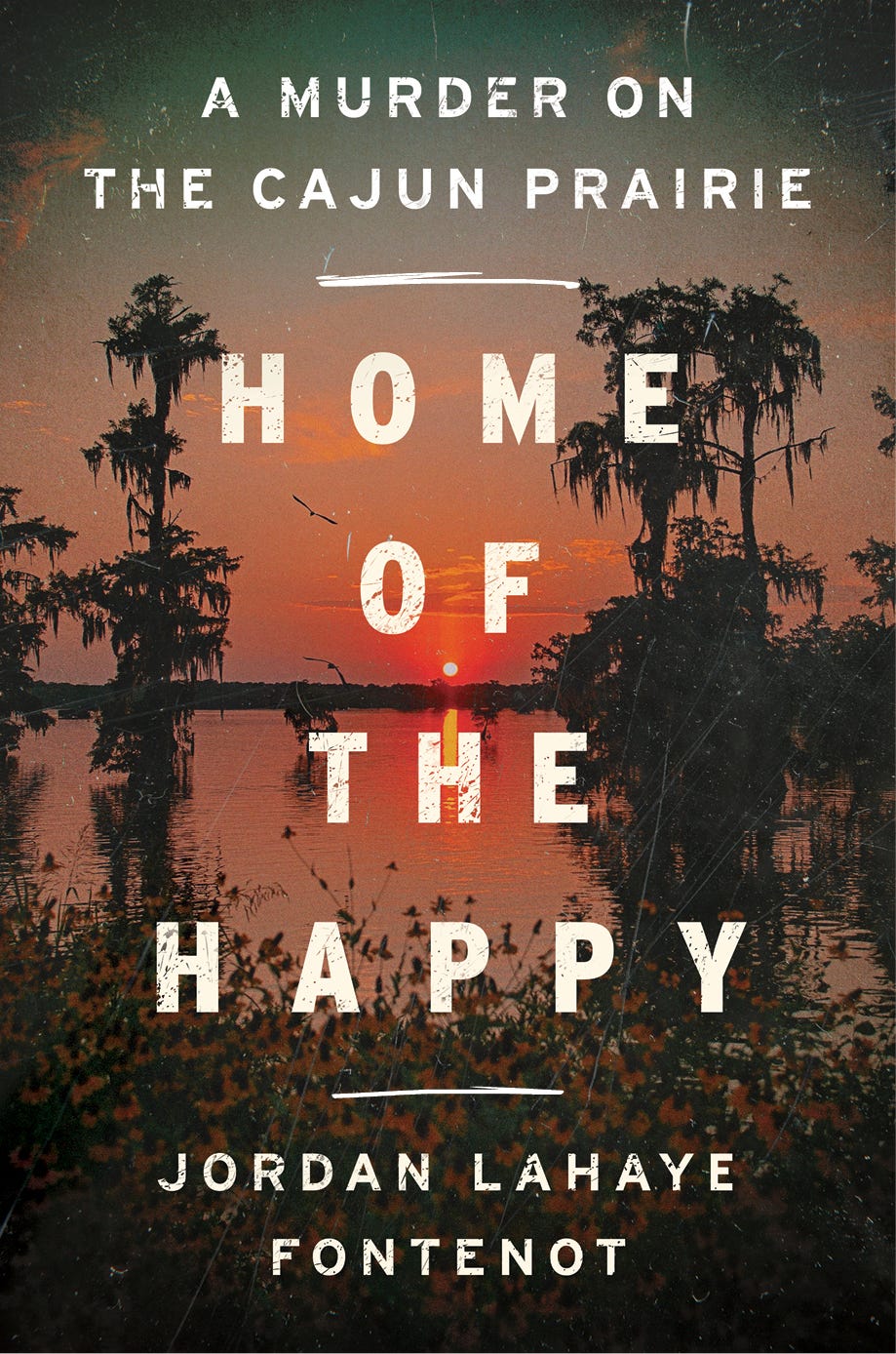

Book News

(Free) tickets are officially live for my book launch on April 1 at Cavalier House Books in Lafayette! From 5:30 pm–8 pm, join me and my dad, Marcel LaHaye, and James Fox-Smith, publisher of Country Roads magazine for a reading and conversation about Home of the Happy, followed by a book signing. Reserve your spot, and a book if you’d like (!), here.

Other Upcoming Book Tour Dates

April 2: Garden District Books in New Orleans, 6 pm

April 3: Cottage Couture in Ville Platte, 5:30 pm

April 4: Books Along the Teche Literary Festival—Shadows-on-the-Teche Visitor’s Center in New Iberia, 10:30 am

April 8: Lemuria Books in Jackson, Mississippi, 5 pm

April 10: The Center for Louisiana Studies in Lafayette, 6 pm

April 12: NUNU Arts & Culture Collective in Arnaudville, 2 pm

April 16: East Baton Rouge Parish Library-Main Branch at Goodwood, 6 pm

April 25: Country Roads magazine launch—at the Conundrum, St. Francisville, 5:30 pm

April 26: Indie Bookstore Day at Cavalier House Books in Denham Springs, 1 pm